I keep finding great new maps of the hill and Roxbury in general, so rather than writing a post for each of them I’m putting together this summary post for easy reference. I’ll add new links as I find them.

If you have a link to a map of Fort Hill that I’m missing (especially any between 1931 and today), please let me know in the comments!

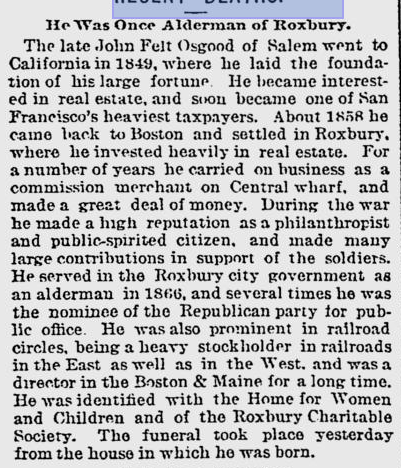

Maps of the Siege of Boston: The earliest maps I’ve found are all of the Siege of Boston. Because of our hill’s prominence in the Siege, various parts of Roxbury are represented on all of these beautiful old maps. Had we not been involved in this military effort we’d be lucky to have even one map of this quality from the 18th century. The First Church is represented on most of these, and some of them show a cluster of buildings around Dudley Square. Many of them show one massive fort, not the two distinct upper and lower forts that we know were here at Highland Park and on the hill next to Kittredge Square. In most of these, the scale is nonexistent, but they are all beautiful. At this time, Roxbury was a tiny farming village of perhaps 2,000 people.

- 1775: A Plan of the Town and Harbour of Boston and the Country Adjacent with the Road from Boston to Concord. (Wikimedia via Library of Congress). A somewhat cartoonish view of the siege from July of 1775 that shows the guns and tents of General Thomas’s encampment.

- 1775: Map of the environs of Boston (Leventhal Map Center at BPL). Appearing August 28, 1775, in the London publication, The Remembrancer, this was one of the earliest British depictions of Boston and vicinity following the battle at Bunker Hill.

- 1775: A Plan of Boston, and its Environs shewing the true Situation of His Majesty’s Army (Mass Historical Society). This map shows Boston and surrounding towns during the Siege of Boston in October, 1775.

- 1776: Carte du port et havre de Boston avec les côtes adjacentes, dans laquelle on a tracée les camps et les retranchmens occupé, tant par les Anglois que par les Américains (Leventhal Map Center at BPL). Highlighted on this fine topographic map of Boston and vicinity are the British and American troops. The American troops are colored red — the first corps in Cambridge, the second corps opposite Charlestown neck, and the third corps near Roxbury.

- 1777: A Plan of Boston in New England with its Environs, including Milton, Dorchester, Roxbury, Brooklin [sic], Cambridge, Medford, Charlestown, Parts of Malden and Chelsea, with the Military Works Constructed in those Places in the Years 1775 and 1776 (Mass Historical Society). Originally published in 1777, this 1907 facsimile printed by Boston publisher W. A. Butterfield reproduces the incredible detail captured by Loyalist Henry Pelham as he surveyed the theater of the Siege of Boston.

- 1777: BOSTON its ENVIRONS and HARBOUR, with the REBELS WORKS RAISED AGAINST THAT TOWN IN 1775, from the Observations of LIEUT. PAGE of His MAJESTY’S Corps of Engineers, and from the Plans of Capt. Montresor. (Boston Rare Maps). One of the most careful depictions of the Boston area executed during the Revolution, taken from surveys made on the spot by British engineers. Yours for only $23,500! Alternate version at the Leventhal Center website.

- 1780: Boston et ses environs (Leventhal Map Center at BPL). Reflecting French interest in the American Revolutionary War, this French publication was copied from a similar map of Boston and vicinity published in London in 1778. The original map was based on the British intelligence of Lieutenant Page.

- 1806: Boston and its environs (Leventhal Map Center at BPL). Based on Lt. Thomas Page’s Revolutionary War era surveys, this very attractive map depicts metropolitan Boston as it appeared at the beginning of the 19th-century.

19th Century Roxbury until its annexation: In these maps, we see Roxbury go from a tiny town of 2000 people to a full-fledged industrial city of perhaps 40,000 or more by 1868. The quality of the maps also improves dramatically over a short period of time. I’ve excluded a number of maps that show only a portion of Fort Hill or that lack any meaningful detail.

- 1814: A Plan of those Parts of Boston and the Towns in its Vicinity: with the Waters and Flats Adjacent (Mass Historical Society). This map by Benjamin Dearborn (1754-1838) is a proposal to construct what he called “Perpetual Tide Mills” across the Back Bay and South Bay in Boston. The plan details water and marshland as well as streets and roads of Boston, Roxbury, Brookline, Charlestown, Cambridge, Brighton, and Dorchester.

- 1832: Map of the town of Roxbury (Leventhal Map Center). The first map in my collection dedicated to Roxbury and covering the entire town, which then included West Roxbury, Jamaica Plain, and Roslindale. Another version of this map is available at the JP Historical Society. A small fold-out version of this map was included in Drake’s History of Roxbury. This is the first map to show Highland Street, which was laid out shortly after the “five investors” purchased their large tract of land on top of the hill.

- 1843: Map of the town of Roxbury, surveyed by order of the town authorities (Leventhal Map Center). What looks like an update of the 1832 edition, but by a different author. A great map to show the rapid growth between during that decade.

- 1849: Map of the city of Roxbury (Leventhal Map Center). An updated version of the 1843 map. This is the first map after Roxbury became a city in 1846, and shows the wards of the new city. This is also the first map where we see Fort Ave.

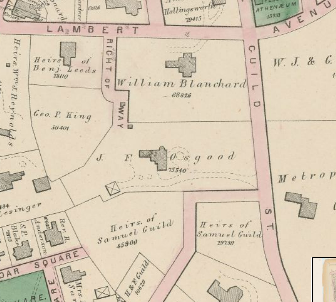

- 1852: Map of the City of Boston and immediate neighborhood (Leventhal Map Center). An absolutely gorgeous map that shows our neighborhood in its entirety. This is one of the first maps to show individual property names and building outlines. It also features etchings of 55 buildings from around Greater Boston around the perimeter of the map.

- 1860: Roxbury (WardMaps.com) A basic street map without much other detail.

Roxbury from 1868 to the 1930’s: After Roxbury became a part of the City of Boston, it continued its massive growth even as it shrank to its present diminished size. By 1940, Roxbury had grown to a population of about 140,000.

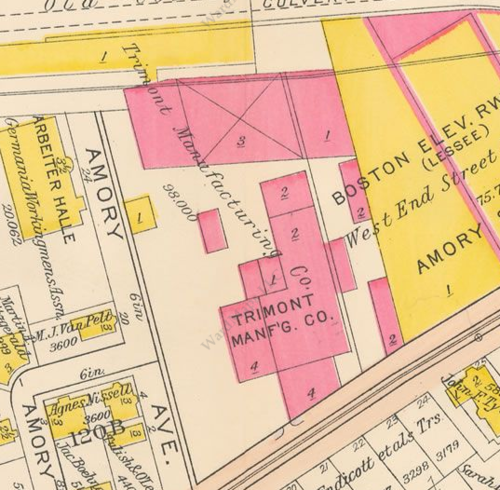

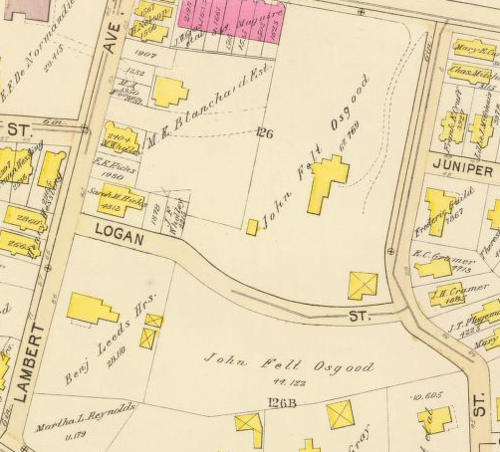

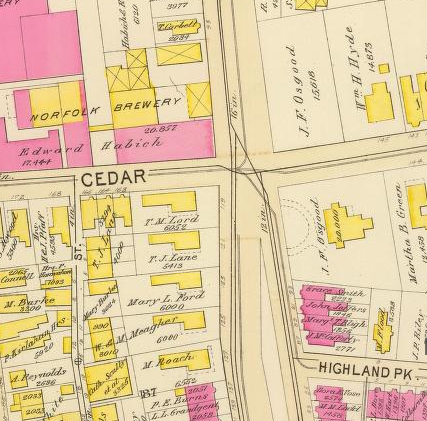

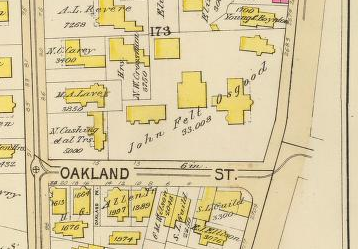

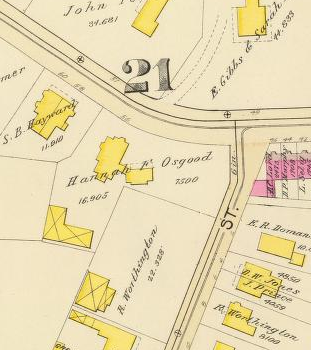

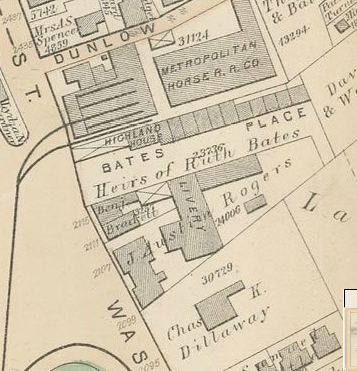

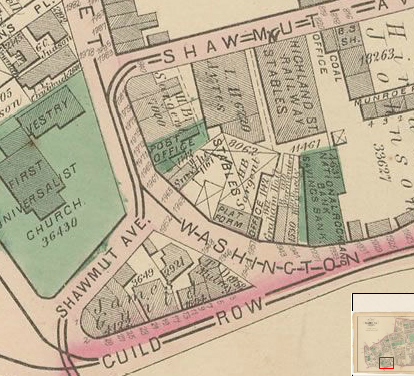

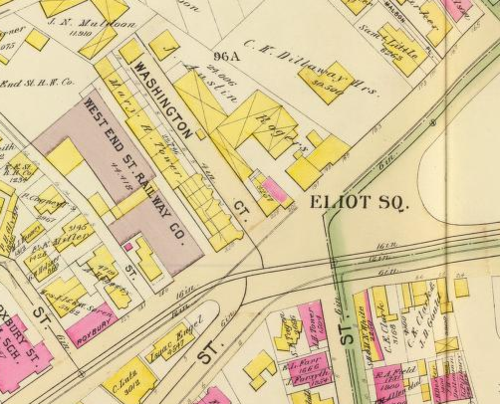

A number of these maps are insurance atlases. These were produced to help insurance companies decide where to write policies and how much to charge for them. The atlases typically have a very small scale and use many pages to cover a neighborhood. Building outlines, street names, ownership, and many other details are rendered in exacting detail. In these atlases, the pink buildings are generally brick and the yellow ones are wood frame-an important distinction for someone considering whether or not to write a fire insurance policy on a particular building!

UPDATED 3/18/2012: Thanks to Mark for the tip on several more atlases available at mapjunction.com, where the atlases have been stitched together and overlaid on current imagery so you can much more easily find what you’re looking for and see changes over time from 1883 through 1931

http://www.mapjunction.com/bra

It takes a little work to figure out, but once you do you can toggle among multiple fire insurance maps for the same site. Follow these links:

New Flash Viewer > wait to load, then:

Add Layer Group >

Boston Public Library >

Bromley Atlases >

Roxbury

- 1873: Atlas of County of Suffolk, MA Vol. 2nd 1873. Available at both WardMaps.com and Historic Map Works.

- 1884: Bromley atlas available at http://www.mapjunction.com/bra

- 1888: Boston Highlands, Massachusetts, Wards 19, 20, 21 & 22 (Leventhal Map Center). One of my favorite maps, this is a birds eye view of Roxbury (or Boston Highlands, as it was temporarily rebranded after annexation). Almost every building in the city, including my house, is visible. The outside of the map is bordered by 40 engravings of prominent Roxbury businesses and cultural institutions showing Roxbury at what I consider to be its peak. Happily, you can buy this map as a print on eBay or at WardMaps.com!

- 1888: Boston 1888 Vol 3 Roxbury (Historic Map Works). This only covers a portion of our neighborhood. The index map indicates that volume 4 has the missing pages, but the site doesn’t have volume 4 for this year.

- 1889: Boston 1889 Vol 4 Roxbury (Historic Map Works) Not to worry about the missing 1888 map, because this one has the whole neighborhood covered.

- 1890: Bromley Atlas of Boston and Roxbury (WardMaps.com)

- 1895: Bromley Atlas of Boston/Roxbury. This atlas is available at the David Rumsey map collection and WardMaps.com

- 1899: Bromley atlas available at http://www.mapjunction.com/bra

- Circa 1900: Boston & Dorchester & Roxbury (WardMaps.com) This looks a lot like a modern street map in coloring and style, but lacks the detail that makes the atlases so enjoyable.

- 1906: Bromley atlas available at http://www.mapjunction.com/bra The Bromley Atlas of Boston/Roxbury is also available at Historic Map Works, minus plate 24, which covers Fort Ave, Beech Glen St., and Highland Park. A handful of pages are also available at WardMaps.com.

- 1907: Map of Dorchester, Roxbury, and West Roxbury (Leventhal Map Center). Not a particularly exciting map, but it does cover all of Roxbury and JP.

- 1915: Bromley Atlas of Boston/Roxbury. Available at http://www.mapjunction.com/bra, Community Heritage Maps, WardMaps.com and Historic Map Works.

- 1924: Boston Zoning Map, Plate 4 (Historic Map Works). The first map I’ve seen that has zoning overlays.

- 1931: Bromley atlas available at http://www.mapjunction.com/bra The Bromley Atlas of Boston/Roxbury is also available at Historic Map Works. This is the last of the wonderful Bromley Atlases that I’ve seen online.

That’s pretty much all I’ve got until we get to the modern maps - there’s a huge hole in my knowledge of the neighborhood from 1931 until the present day. Sadly, much of this is due to insane copyright terms, but that’s a story for another day. But there are a few other maps worth noting:

- 1988: Image and New Development: Highland Park (Harvard School of Design)

- 2001: Painting With Maps, Highland Park(Mapsovertime.com)

- 2010: Boston Census Data (City of Boston)

- 2011: Boston’s Lost Breweries (Google map with my notes)

If you have any access to maps from the years in between 1931 and 1988, I’d love to see them. And if you find anything at all that covers a significant part of Fort Hill, please send me a link or leave one in the comments so I can keep this up to date.