I posted earlier about the 1858 edition of this directory available online via Google Books. Now here’s the 1866 edition for your browsing pleasure. This was likely the last edition, since Roxbury became a part of Boston in 1868 and the directory was published biannually.

Stand up against Internet Censorship: Stop SOPA! /

If you enjoy this blog, and reading about history in general, it’s urgent that you join millions of others to call your representatives in the house to stop a bill called SOPA (the Stop Online Piracy Act). This bill is a censorship bill that threatens to destroy the internet as we know it by criminalizing all kinds of activities we now take for granted, like linking to copyrighted works and posting snippets of those works in blogs. The type of research I’ve been doing online will be directly impacted. The bill is terrifying not just for what it tries to prohibit and the insane penalties it proposes, but also because it bypasses due process and allows for-profit companies to decide that they can simply make certain website disappear.

All of this is being done to prop up the government-granted monopolies that we have given through copyright laws to the music and movie industries. Roxbury played a crucial part in the struggle against unjust monopolies in the Revolutionary War and it’s time for us to go back to our roots and stand up against them now.

The many problems with the bill are nicely summarized in this NY Times Op-Ed piece.

Bacon's Dictionary of Boston, 1886: The Roxbury Entry /

In my perusings of Google Books I’ve found some reference gems. One of the best is Bacon’s Dictionary of Boston (1886 edition), an invaluable book of the sort that makes historians weep for joy. It’s got clear explanations of many of the old mysteries of Boston, and it gives a delightful sense of what Boston was like towards the end of its decades of breakneck development in the latter half of the 19th Century.

Rather than try to summarize the wonderful entry on Roxbury, I’m simply going to reproduce the whole thing here. It starts on page 351 if you want to see the original. Happy reading!

Roxbury District (The). The first settlers of Roxbury, some say, were of the company from Dorchester, England, who came over in the ” Mary and John,” and founded the new Dorchester, now the Dorchester District of the city. [See Dorchester District, and Old Harbor Point.) But the principal settlers were of those who arrived a month later in the Arbella. They first called the place ” Roeksbury,” — or Rocksborough; and it was recognized as a town by the Court of Assistants on Oct. 8, 1030. Here Thomas Dudley afterwards settled. The Universalist Church, Rev. Dr. Patterson, now occupies the site of his house. Three years after the settlement of the town, in 1033, William Wood thus described its appearance: “A mile from this towne [Dorchester] lyeth Roxberry, which is a fair and handsome Countrey-towne; the inhabitants of it being all very rich. This Towne lyeth upon the Maine so that it is well woodded and watered; having a cleare and fresh brooke running through the Towne. Vp which although there come no Alewines, yet there is a great store of Smelts, and therefore it is called Smeltbrooke. A quarter of a mile to the North side of the Towne is another river called Stony-river, upon which is built a watermilne. Here is good ground for corne, and medow for cattle. Vp westward from the Towne it is something rocky whence it hath the name of Roxberry. of Cattle, impaled Corne-fields, and fruit“‘tl Gardens. Here is no Harbour for ships, because the Towne is seated in the bottome of a shallow Bay which is made by the necke of land on which Boston is built; so that they can transport all their goods from the Ships in boats from Boston which is the nearest Harbour.”

The town originally included the present West Roxbury District (set off in 1851), with Jamaica Plain; and the present town of Brookline, known in the early days as ” Punch Bowl Village.” The first church was founded in 1632 [see First Church in Roxbury]; and 13 years after the settlement of the town, the “Free Schoole in Roxburie” was established. Roxbury long remained a”faire and handsome countrey-towne.” Until well into the present century it was a picturesque vilage, with a single bustling business street, a few manufactories, clusters of houses about the ” centres,” and outlying farms, some of them with fine old-fashioned homesteads occupied by descendants of the original proprietors of the lands.

During the Revolutionary period it had scarcely 2,000 inhabitants, a little over 200 dwellings, three meeting-houses, and five schools. In 1800 the population had increased to only about 2,700. Twenty years after the population is given as 4,135. During the next 10 years many improvements were made. In 1824 Roxbury Street, now Washington Street, and then the one thoroughfare through the town, was paved, and brick sidewalks laid; the next year the several roads were given names as streets; the same year the Norfolk House was opened; the first newspaper was then started, — the ” Norfolk Gazette.” In 1827 hourly coaches began to run between the town and Boston, — the first in this part of the country. In 1830 the population was about 5,247. During the next 10 years the growth was more rapid. Many new streets were laid out, business extended, and new buildings and new dwellings were erected. In 1840 the population was 9,089. Six years after, the town government was abandoned, and the place became a city. In 1850 it had 18,373 inhabitants. In 1856 the first street railroad was established; cars running, at the beginning, from Guild Row to Boylston Street in Boston. In 1807, when it was annexed to Boston, and became the Roxbury District, it had a population of 30,000; and its property was valued at $18,265,400 real, and $8,280,300 personal, a total valuation of $26,551,700. [See Annexation.] In 1870 its population was 34,772; and in 1880, 78,799.

Though it has expanded and grown metropolitan of late years, the Roxbury District is to-day one of the most attractive portions of the city, with beautiful walks, fine drives, broad shaded streets over its hills and through its vales, lined with pleasant dwellings, — few unsightly blocks, but mostly detached houses, many of them with neatly laid-out grounds and trees about them, and not a small number extensive estates with fine lawns and large gardens. In an early edition of “Hayward’s Gazetteer,” it is said of Roxbury: ” A great degree of taste and skill has been displayed here, both in horticultural and architectural embellishments, for which the ‘highlands’ in the southern part of the city, especially furnish a beautiful advantage. Many parts of Roxbury, which until recently were improved as farms or rural walks, are now covered with wide streets and beautiful buildings. Several of the church edifices in Roxbury, being located on elevated positions, make a beautiful appearance.” As complimentary language can be employed in describing the Roxbury District of to-day.

A few of the old landmarks of Roxbury yet remain, the most noteworthy of which are mentioned in the paragraph on ” Old Landmarks” in this Dictionary. The Cochituate stand-pipe, on the hill between Beech Glen Avenue and Fort Avenue, stands on the site of the earthworks thrown up in June, 1775, and known as the “Roxbury High Fort.” This fort was built under the direction of Gen. Thomas, and crowned the Roxbury lines of investment at the siege of Boston. This was the strongest of the several Roxbury forts, others of which guarded the only land entrance to Boston, which was over the Neck (see Neck, The Boston], defended the road to Dorchester, covered the old landing place, and commanded Muddy River. The steeple of the First Parish Meeting-Honse was the signal station of the besieging army on this side, and was a conspicuous mark for the enemy’s cannon.

Roxbury, small as it was, had a conspicuous part in the early events of the Revolution. It was the native place of the immortal Warren, and of Heath and Greaton, generals in the Continental army. Gen. Horace Binney Sargent, in his oration on the occasion of the Roxbury celebration in November of the centennial year of 1876, recalled the meetings of the Sons of Liberty in the Greyhound Tavern in Roxbury Street, where Graham’s block now stands. “Its walls rang with wit and patriotic eloquence.” Greaton, the inn-keeper, who afterward became a brigadier-general in the army, was at Lexington and Bunker Hill. The first “general order” for the army was signed by Heath, who was the son of a Roxbury farmer. He was at Lexington and Bunker Hill, and commanded a part of the right wing in the siege of Boston. Later he was appointed to the command of West Point by Washington, after the treason of Arnold. Mosea Whiting and William Draper of Roxbury commanded companies at Lexington, and 140 Roxbury men were there. Robert Williams, master of the Latin School, “changed his ferule for a sword,” taking a commission in the army. Major-Gen. Dearborn, on the staff of Washington, lived and died in Roxbury.

Glimpses of Early Roxbury /

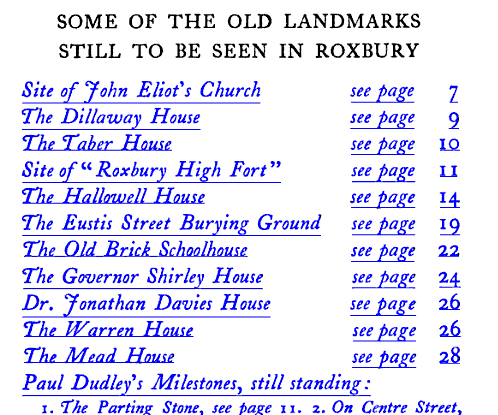

In 1905, the Daughters of the American Revolution put together this concise little guide to the landmarks of Roxbury. This book is all about the buildings and geography of historical Roxbury, with lots of interesting asides about who did what and lived where. As a future project, I might convert this to a google map and excerpt the text to accompany the mapped locations.

Roxbury Magazine 1899 /

In 1899, the All Souls Unitarian Church published this “magazine” about Roxbury. While it’s similar to a modern magazine in terms of style, layout, and the length of the articles, it doesn’t appear that this was a recurring periodical. There is only this one issue that I can find.

For those looking for a quick summary of the history of Roxbury, this is probably the best place to start. The contributors were a who’s who of Roxbury society at the time, with articles by Edwin Upton Curtis, Edward Everett Hale, Reverend Lyon, and many other municipal leaders. The issue is packed with pictures of local attractions, including a number of historic houses and plenty of pictures of Franklin Park, then a relatively new park that was the pride of Roxbury.

But the real prize in this volume is the compilation of stories about Roxbury. There’s a wonderful history of the First Church and John Eliot, a series of short biographical blurbs about all of the famous men of Roxbury to date, Rev. Hale’s description of Roxbury in 1775, lists of institutions and landmarks, and more. Clocking in at just 50 pages, this is probably the best introduction to the history of Roxbury you could ask for. It covers a great deal more than Fort Hill, including a history of the utopian Brook Farm. Available free online through Google Books, but worth buying as a reprint from Amazon or the Harvard Coop.

The death of Annie Thwing /

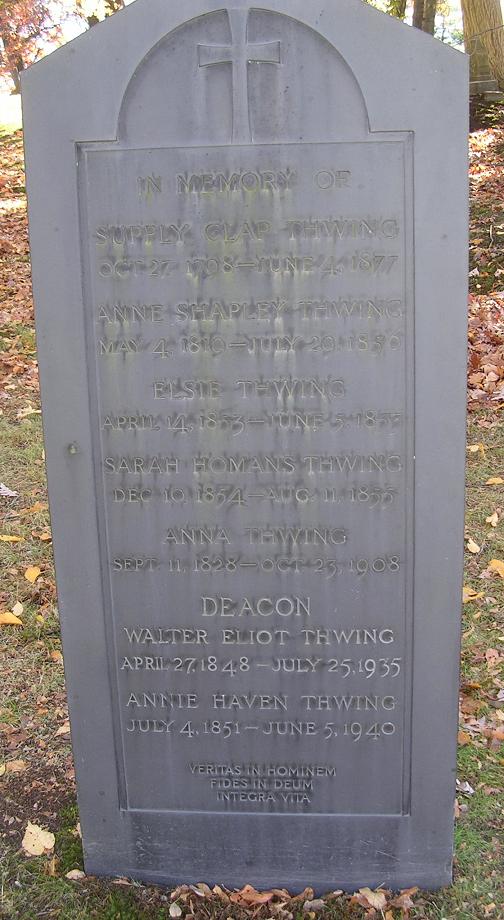

I’ve written before about the Thwing family, but today I came across some more information. In July of 1856, the Thwing family was traveling, possibly on vacation. They traveled by coach to the shores of Lake George at Ticonderoga, where they boarded a 140’ steamer with a paddle wheel on each side. The ship had been delayed for several hours by late-arriving passengers and was pushing hard to make up time.

Not long after leaving, traveling at the then-rapid pace of 10 miles per hour, the ship’s engine room caught fire. The ship’s small crew steered the boat, which was just a short distance from land, towards the shore but there was panic among the 80 or so passengers. The ship had no functioning life preservers and only one lifeboat, which Supply Clap Thwing is reported to have tried and failed to launch before the fire reached it and burned it in place.

As the ship approached land it struck a rock and stopped abruptly. Parts of the ship were in shallow water, while others were in much deeper water. Several passengers either jumped or were thrown off the deck by the collision, and 7 women died. If I had to guess, I would say that the women were likely to have been wearing large dresses with several layers of undergarments, so they probably never stood a chance in the masses of heavy, wet clothing.

Among the dead were Supply’s wife Annie and her sister Caroline Belknap. Young Walter Eliot, then just 7 years old, survived the incident along with his father but unfortunately had to witness his mother’s drowning. The paper doesn’t say if young Annie Haven, who was 5 years old at the time, was also on board but it seems likely that the family was traveling together. A young girl was reported to have been placed on top of a box and floated to shore—the box contained a number of rattlesnakes belonging to one “old Dick, the rattlesnake man.” The girl and snakes all survived. It’s pure conjecture on my part to guess that this might have been Annie Haven, but it’s possible.

Annie and Caroline were given a service at the First Church presided over by Reverend Putnam. Annie is buried at Forest Hills Cemetery in the family plot. I don’t know Caroline’s final resting place but there’s a good chance that she is also at Forest Hills.

This must have been a tremendous blow to Supply Clap, especially as he had lost 2 infant daughters, one in 1853 and the other just a year earlier in 1855. But he went on to recovery and lived another 21 years. Walter lived on until 1935 and Annie Haven made it until 1940 at her home at 65 Beech Glen St.

There’s an interesting first-hand account of the disaster, complete with a heartbreaking description of Walter’s attempts to wade into the water to save his mother, in the New York Times. There’s also something of a rebuttal to that version of things that attempts to portray the captain and crew of the John Jay in a slightly better light.

Mayor Flynn's Neighborhood Action Plan for Highland Park /

Here’s a link to the 51-page action plan that Mayor Flynn’s Public Facilities Department (PFD) put together for Highland Park in 1989. The plan sounds similar in many ways to what we hear today. PFD wanted to build affordable housing, maintain neighborhood stability, preserve the unique character of our neighborhood including preserving and maintaining our green space, and involve residents in decision-making. Sound familiar?

The plan lists dozens of abandoned city-owned parcels, many of which are still vacant today, others which have only been developed in the last few years. Almost laughably, PFD lays out a strategy to develop most of them through a six-month disposition process. Had that happened, we’d be celebrating the 20th anniversary of 12-16 units units in the vacant lots across from the new police station, 25 units in the large vacant lot on Blanchard and Bartlett next to the Norfolk House, 32-35 units on Cedar between Centre and Highland, and 12-15 units in the vacant lots on Valentine.

Also, if everything had gone according to plan we’d be celebrating the 20th anniversary of a revitalized Dudley Square, there would be a hotel and office complex on Parcel 18 in front of Ruggles T station, and the mosque would be about 15 years older. Seems the more things change, the more they stay the same.

One last item of note is the proposed walking trail from Eliot Square to the standpipe, an idea that first came up in the mid-1970s as part of RAP’s efforts to redevelop the area. This is a great idea and perhaps it’s time we brought that, along with some of the other long-delayed developments, to fruition.

Reminder: Meet Wed night at 7 to decide on history to feature at AK Park! /

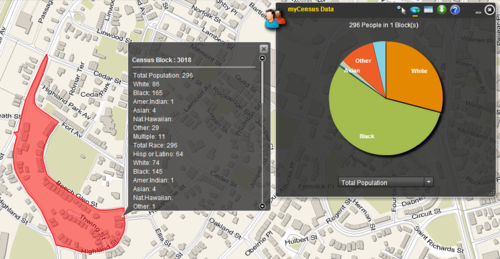

2010 Boston Census data mapped! /

Via the JP Gazette, I bring you the myNeighborhood Census Viewer, a fantastic new mapping application from the City of Boston. It’s a simple way to get info about any census block or group of census blocks in the city. Simply click on any area and you’ll see the census block highlighted, with all of the stats that the census collects on race, gender, age, household status, etc., displayed right there. You can also select multiple blocks through a variety of tools. It’s also a beautiful basemap with building footprints. Perfect for the armchair sociologist, historian, or cartographer!

Here’s a view of the info for my census block.

The Boston Directory, 1873 /

Following up on my last post about the Roxbury Directory of 1873, here is another edition from just after Roxbury was absorbed by Boston. Obviously, this one is much larger (over 1300 pages!) so it’s harder to search and it covers Boston and all of the towns that had been absorbed by it as of 1873. But it’s another arrow in the quiver for historians and once again the advertisements will be entertaining for everyone.

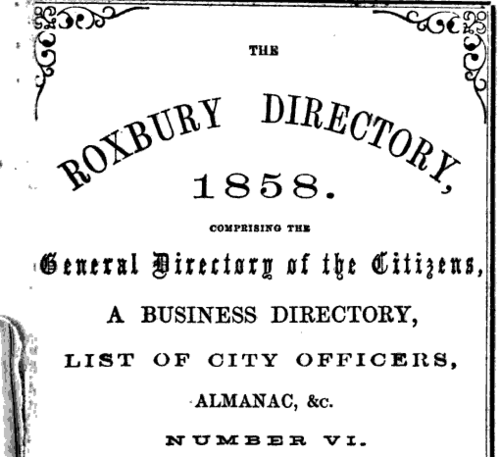

The Roxbury Directory, 1858 /

The Roxbury Directory was a biannual directory of people and businesses in Roxbury, something like a phone book only well before Bell got around to inventing the phone. Google has a copy of the sixth edition, from 1858, which contains the names, addresses, and occupations of about 5500 Roxbury residents as well as information about the taxes they paid (which gives us an indication of their overall wealth) and dozens of period advertisements for Boston and Roxbury businesses.

This is a great resource for historians and it will be fun to flip through the ads for pretty much anyone. Enjoy!

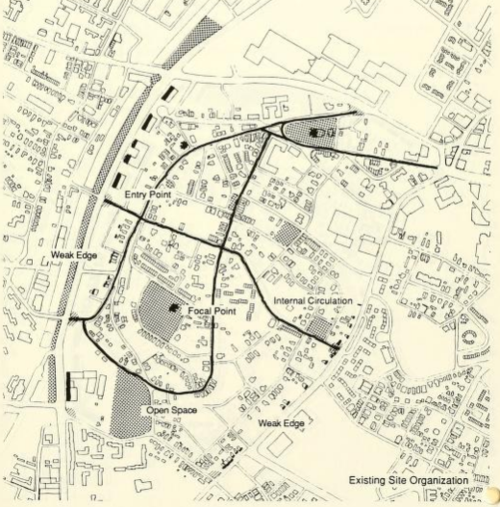

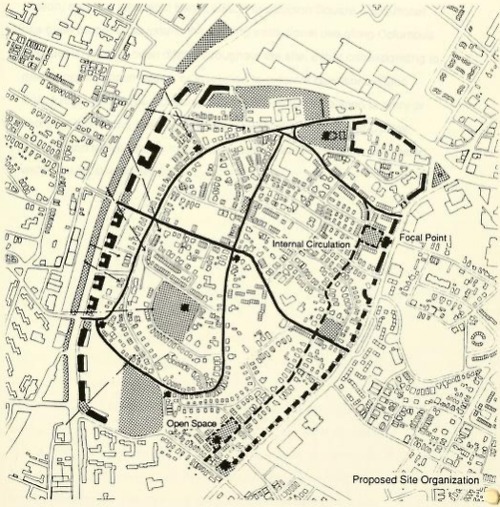

Image and New Development: Highland Park /

Here’s a link to a graduate thesis for the Harvard School of Design written by Master’s candidate Anne Burns in 1988. The thesis, while clearly a scholarly exercise, presents a great overview of the issues that were facing Roxbury and Highland Park nearly 25 years ago. It should be required reading for anyone who wants to discuss redevelopment in the area today, especially for the redevelopments scheduled at Bartlett Yard and Jackson Square.

The thesis starts out with her reasons for choosing Highland Park as a subject area, a brief but well-done history, and then jumps right into some of the issues the neighborhood was facing in the mid-80s. In some ways, things couldn’t be more different, and in others they haven’t changed at all.

The biggest difference is that at the time, a huge proportion of Highland Park was still distressed but there was finally a significant amount of renovation happening. While we still have a handful of vacant buildings and there are many occupied buildings that could use a little sprucing up, I think it’s fair to say that the neighborhood has long since recovered from the worst of the population decline of the late 60s and early 70s.

The similarities are perhaps more striking. Ms. Burns notes that residents of the neighborhood tend to have a much higher opinion of the area than outsiders. She notes that despite this, people who do not live here were in charge of decisions that would have huge impacts on those who did. And she discusses some of the reasons for this from an architectural point of view, discussing the way our community presented itself to the outside world from those places that the outside world would most likely see it: along Columbus Avenue, Washington Streeet, from Roxbury Crossing and Jackson Square T stations, and along Malcolm X Boulevard.

She also notes that the residents were cautiously optimistic about the amount of redevelopment and new development taking place at the time. They wanted something that felt unified, cohesive, and well-planned. They feared piecemeal development that didn’t fit the character of the neighborhood, such as large public housing towers being dropped onto sites right next to one and two-family houses. They also wanted to maintain and celebrate our neighborhood’s many historical sites. Hopefully all of this sounds familiar to those of us who are engaged in shaping Highland Park today.

After the discussion of why and how she will look at the neighborhood for redevelopment, the thesis dives into a GIS exercise. Given the primitive nature of GIS software at the time, this is a pretty impressive undertaking, with page after page of detailed maps showing historic buildings, rowhouses, institutional structures, primary and secondary roads and traffic patterns, and vacant land.

She notes historic areas and viewpoints, and denotes the “spheres of influence” of the First Church and the Standpipe. After all of this, she makes a development proposal focusing on new development in 5 key areas: the area where the mosque now sits, the area around the corner of Shawmut and Malcolm X, the Bartlett Yards area, the cluster of vacant lots around Thornton and Valentine, and the empty space along Columbus (including the RCC parking lots).

She takes great care to propose developments that will unify the neighborhood, siting larger institutional uses as a “hard edge” along Columbus and preferring residential-scale 1-3 families on Washington and in the Thornton Street parcel. I won’t go into full detail here, but it’s a fascinating read and many of her analyses and decisions still hold up almost 25 years later.

Sadly, many of these parcels are still vacant, but as we continue to discuss what should go where, I’d suggest taking a fresh look at this document. There is a lot we could bring into the current planning process.

Inside the Cochituate Standpipe /

Our neighbor Derek Lumpkins was lucky enough to get a peek inside the standpipe a couple of years ago. He took this handful of pictures and shares them on his flickr account.

Report of Joint Special Committee on Sewerage to the City of Roxbury, 1858 /

Here is a link to a report to the short-lived City Council of Roxbury detailing the possible locations of city-owned sewers. In my day job, I am a water professional with a special focus on wastewater, so this report is near to my heart. We are blessed to have a functional water and sewerage infrastructure in this country, largely thanks to the efforts of people 100 or more years ago—people like the authors of this report. Since most of us have never known water scarcity or experienced waterborne disease, we tend to take these public works projects for granted.

One of the reasons settlers chose Roxbury in the 1630s was its pure source of water at the Smelt Brook. The Smelt Brook, long since entirely culverted and forgotten, was named for the abundant smelt that populated it. As described in this book, it started at May’s Pond (which has also been wiped off the map) near the intersection of Quincy and Warren Street. It wound its way through the flat area that is now the Mall of Roxbury and the houses just west of it, past the intersection of Walnut and Dale by the northeast corner of Malcolm X park, and flowed along the path of what is now Washington Street towards Dudley. Unfortunately, that brook went on to become a sewer, as did so many others including the nearby Stony Brook.

This report is interesting for a number of reasons. First, it paints a picture of Roxbury in the middle of its years as a city, during a period of rapid growth, a city struggling to build new infrastructure as it changed from a small farming town to a major industrial center. It’s also a fascinating snapshot of Roxbury in 1858, before the filling of the Back Bay and South Bay, when the town still had water borders and a town dock. And of course, it’s a gold mine for sewer nerds like me.

Bear in mind when you’re reading this that many of the street names have changed or streets have been rerouted since this pamphlet was written. For instance, what we now call Washington Street was then Shawmut Avenue. What is now Roxbury Street was then Washington Street. The closest map I know to this time is from 1873, and although things were changing fast the map and report are close enough in time to be useful to each other. If you’re confused, a look at the index map might be helpful.

Update to the Boston Belting Company /

I stumbled across this biography of James Bennett Forsyth while researching something else entirely. Mr. Forsyth apparently grew up in the offices of the Boston Belting Co. factory where his father worked and eventually went on to become its director and to hold over 50 patents relating to vulcanized rubber. In fact, it would appear that all modern firefighters owe a debt to him and the company for inventing rubberized fire hoses. Click through for a brief but fascinating read about one of our forgotten residents.

Wednesday, 12/7 meeting to identify historic figures for new Kittredge Park Art! /

Via Chris McCarthy, who is central to the campaign to renovate Kittredge Park, I bring you the invitation below to join us at a public meeting. Chris has been kind enough to invite me to help identify important historical events, places, and people for this project but we need to hear from a lot more people.

Please join us at the event below. If you can’t make it, send me a note or leave a comment on this thread with your ideas for important local historical figures and events. We are especially interested in more recent history like the story of Ed Cooper, RAP, the fight against I-95, etc.

—————-invitation below——————

The restoration of Alvah Kittredge Park is now well underway. One of the outstanding tasks for this project is for the community to identify the historical figures and events we’d like to celebrate within the art commissioned for the park by the E. I. Browne Fund. This grant also funds our commission with artist Ross Miller who has been working with us since January on this project. Please join Ross and community members at the Cooper Center on Wednesday, 12/7 to help us identify the local history that is important to you. We are hoping that our commissioned art can celebrate these events and generate a broader interest and understanding of how they’ve shaped our community. Please bring to the meeting any interesting materials you may have to contribute to this effort. And invite your neighbors please!

When: Wednesday, December 7

Time: 7:00 to 8:30 PM

Where: Cooper Center, 34 Linwood Street

Yum: Refreshments will be served

Related links:

- Friends of Alvah Kittredge Park: www.facebook.com/friendsakpark

- Story on our commission with Ross Miller: http://www.boston.com/yourtown/news/allston_brighton/2011/01/familiar_local_artist_commissi.html

- Jason Turgeon’s Fort Hill History blog: http://forthillhistory.tumblr.com/

The following is the purpose statement included in our original application to the E.I. Browne Fund. We welcome inclusion of contemporary historic figures and events.

“We believe that Alvah Kittredge Park warrants a reinvestment that befits this historic neighborhood. Our proposed park design celebrates the achievements of our local historic figures. These achievements were the product of their patriotism, ingenuity, artistry, and learning. By restoring this park, we hope to inspire ourselves, and the generations that follow, to embody these virtues. The historic references that will unify our park celebrate the contributions of these historic figures who inspire us to contribute, in each our own way, to the goodwill of the community.”

The Thwing Family and Estate /

Some names are immediately recognizable to all Fort Hill residents. Alvah Kittredge, William Lloyd Garrison, John Eliot, and Nathaniel Bradlee all roll off our tongues. But one of our most long-lived family names has been largely forgotten, with the nothing but a cul-de-sac to remind us of their past glory.

The cul-de-sac, of course, is Thwing Street, a short stub of a street etched into the steep slope of the hill off Highland Street just before it meets Marcella. It represents all that is left of the once-grand Thwing estate, shown here in 1873 at the height of its glory.

The Thwing name goes all the way back to the early years of the Puritans. In 1635 young Benjamin Thwing, at the tender age of 16, hitched a ride across the Atlantic along with his wife Dorothy (who may have had to ride on a separate boat) as a servant or apprentice to Ralph Hudson in Boston. He and Dorothy had seven children, and those children that survived had broods of children of their own, and so on until the Thwing name was spread across the young country. We know all this because in the eighth generation of Thwings there was a man named Walter Eliot Thwing (note the Eliot name, a nod to Roxbury history).

Walter Thwing was a genealogist of the first order, and in an era without the internet or Fedex or telephones he was able to catalog the lives and fates of hundreds of his relatives, including a fair bit of research into the Thwing name in the UK. His magnum opus, Thwing : a genealogical, biographical and historical account of the family, takes us deep into the family history and its relationship with Roxbury circa 1883. Some 20 years later, he published the History of the First Church of Roxbury.

Walter was a true son of Roxbury. According to his brief autobiographical statement in the genealogy, he was born in a boarding house on Cedar St., went to a series of local private schools before attending Roxbury Latin, and managed to get into Harvard before he dropped out to work for his father. The day after Christmas, 1870, he boarded a ship bound for California and kept on going around the world with stops in China, Japan, India, Egypt, mainland Europe, and England before returning home two years later. He claims to have been the youngest man ever to have been around the world at that time. He lived at the family estate on Highland Street with the brief exception of a move to JP for a few years at the end of the 1870s.

Walter’s interest in history was not to be outdone by his sister Annie Haven. Born on the auspicious date of July 4, 1851, Annie’s love of history bordered on the obsessive. She is well-known among historians for her book, The Crooked and Narrow Streets of Boston 1630-1822, but probably should be better known to the rest of us as the author of the classic children’s story Chicken Little. Her crowning achievement, though, was her creation of a massive 74-drawer card catalog detailing every bit of the history of Boston she could track down. Thanks to the wonders of computers, historians can now use a searchable database of her work as they research Boston history. She also created a 3-D model of the City of Boston as it looked in 1775 and traced back her family on the Haven name as far back as 1372. Ms. Thwing lived in Fort Hill, probably at the family house at 65 Beech Glen Street, until her death in 1940. She is buried at the Forest Hills Cemetery in the family plot. The Forest Hills Trust has a more detailed bio of her at this link. She also warrants her own page on wikipedia.

65 Beech Glen Street, the home of Annie Haven Thwing, as it appeared in the April 2, 1881, edition of American Architect and Building News.

Walter and Annie were the children of Supply Clap Thwing. The wonderfully-named man was born on October 27, 1798, in what is now Post Office Square. Supply Clap was a family name; according to the meticulous records of his son he was named for a distant ancestor, Roger Clap, who, “during a famine in the town, had a son born on the same day supplies were received from England, and showed his gratitude by naming his son Supply Clap.”

SC Thwing was a well-to-do man with businesses in the mercantile trades between the East Indies and New Orleans, partial ownership shares of ships, and even business in the coal trade later in his life. He moved to Roxbury in 1824 and never left. He was a pillar of the community, becoming a deacon of the first church, a trustee of Roxbury Latin, and a VP of a local bank, the Institution for Savings in Roxbury and Vicinity. He and his family lived in a beautiful house at 177 Highland at the corner of Beech Glen and Highland St, sadly long gone and replaced by a somewhat drab triple decker on roughly the same spot. He’s seen below standing in front of the wall. Annie Haven and Walter are on the steps.

One final note about Supply Clap: He was a dear friend of Caleb Fellowes, the subject of a future post. When Supply found out that Mr. Fellowes had arranged to leave him a large part of his fortune as part of his will, SC urged him to leave the money to charity instead. That money became the endowment for the Fellowes Athenaeum, known to you and me as the original Dudley branch of the Boston Public Library.

By 1895, the Thwing Estate had been largely sold off and built out and Thwing Street had been added to the maps.

The Boston Belting Company, Roxbury India Rubber Company, and Charles Goodyear /

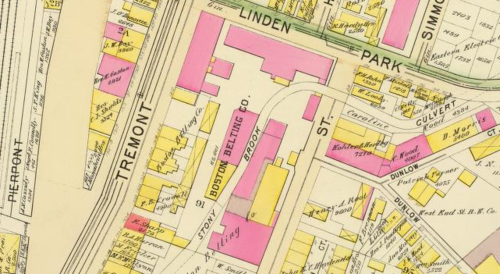

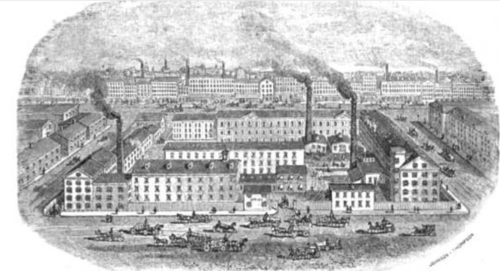

The Stony Brook provided water for more than just breweries. There were dozens of other industries located along its meandering path. One of the first most interesting was the Boston Belting Company. The company was one of our earlier industries, chartered in 1828 along the Stony Brook, in approximately the present-day spot of the Reggie Lewis Center and the Islamic Society mosque.

The Boston Belting Co in 1895. The site was located about where the Reggie Lewis Center and the intersection of Malcolm X and Columbus Avenue now are.

Just a few years earlier, sometime about 1820, a sea captain had brought back a pair of rubber shoes from his travels to Ecuador. Boston being a cold, wet place much of the year, people immediately seized on the utility of rubber boots and shoes. Since rubber could be had for next to nothing and the shoes could be sold for $2 a pair or more, there was something of a speculative boom in the rubber shoe market, soon followed by other rubber products. The Roxbury India Rubber Company was born, led by Edwin Marcus Chaffee, and as much as $2 million in stock was sold based on the promise of the sale of thousands of pairs of shoes and other rubber goods.

An 1880s-era ad from the collection of the Davistown Museum.

In the early 1830s, a bankrupt Philadelphia inventor named Charles Goodyear passed by the Roxbury India Rubber Company’s storefront in Manhattan and bought an inflatable rubber life preserver out of curiosity. Being an innovative sort, he quickly devised an improvement for the flimsy inflation tube and offered to sell his improvement to the Roxbury Rubber folks. Unfortunately, the proprietor told him a tale of woe: rubber, while a fine product in Brazil, was lousy for the Northeast US. It was rock-hard in the winter, and turned into a gummy, stinking mess by the time July heat came around. So many outraged customers had returned products that the company’s directors had been forced to bury the stinking mess of rejects in a pit in the middle of the night.

Goodyear, dismayed, returned to Philadelphia and was promptly tossed in jail for nonpayment of debts. He asked his wife, who must really have seen something in him to stick with him through all of his adventures, to bring him some rubber and a rolling pin and whiled away his time behind bars experimenting with the substance. Eventually he was released and continued his experiments through a series of failures and poverty in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston.

Goodyear ended up as something of a charity case in Woburn, where in 1839, more than 5 years after his fateful purchase of the life preserver, he stumbled upon “vulcanization,” the combination of heat and sulfur that would stabilize rubber and revolutionize life as we know it. Life didn’t get much better for Mr. Goodyear after that, though, as he suffered health effects from the noxious chemicals he experimented with, made pathetically bad business decisions, and found himself embroiled as the plaintiff in literally dozens of patent lawsuits at home and in the UK. His whole sad story is recounted in great detail at a number of places around the web. If you want more info start with the official Goodyear company history, then moving on to “Jacksonian Memories #55.”

It’s not exactly clear what happened during those mid-1830s years in Boston, but he certainly worked with E.M. Chaffee and the proprietors of the nearby Boston Belting Company. In fact, after he finally patented his vulcanization process in 1844, the Boston Belting Company briefly changed its name to the Goodyear Rubber Company before changing it back a couple of years later. Chaffee was forced to sell a $30,000 rubber machine for just a few hundred dollars in the early 1840s, before Goodyear had perfected his process.

Chaffee, Goodyear, and Henry Edwards, the apparent proprietor of the Boston Belting Company, continued to cross paths routinely, with things culminating in an 1850s patent case featuring Chaffee as the plaintiff and the Belting Company as the defendant, which Chaffee eventually won on appeal. The patent in question had originally been given to Goodyear, who had licensed it to Edwards.

Unfortunately for poor Charles Goodyear, he continued to bounce in and out of poverty - and debtor’s prisons - until his death at age 61 in 1860. Fortunately for his long-suffering family, some of his patent royalties eventually panned out after his death and they were able to live in relative ease. The company that bears his name has nothing to do with him. It was started in 1898 and named in his honor. Chaffee’s fate is less well-documented.

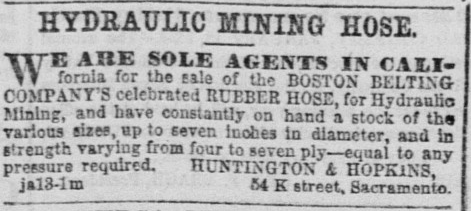

The Boston Belting Company, thanks to the pioneering work of Goodyear, went on to thrive for many more decades making a huge variety of belts, hoses, and other rubber goods. Here’s an ad from the February 9, 1863, edition of the Sacramento Daily Union:

And the firm’s entry in the 1889 “Illustrated Boston" gushes about the firm’s pre-eminence in the global rubber trade and the 2-acre site with 400 employees, as shown here from its entrance on Linden Park Street (a street which has been obliterated by urban renewal along with the factory). It’s hard to believe that our neighborhood was once home to the world’s largest industrial rubber manufacturing operation, or that this operation spawned a massive rubber industry in Massachusetts, but it did.

The firm had a long and colorful history, including a near-disaster due to poor management (PDF) from one John Tappan in 1878. The company was also involved in a long-running lawsuit against the city for altering the Stony Brook, which it had used since 1828 as a source of water and power for its operations. The alterations to the brook took place in 1874, but the lawsuit dragged on until 1903. It also survived some intense competition, including the 1892 formation of the Rubber Trust by the US Rubber Company. The firm was still going strong in 1916, when it was reported to have assets of $2 million and pay 8% dividends, and this 1923 advertisement in Forbes celebrates its 95th year. After that, the trail goes cold.

If you have any more info about the final chapter of the Boston Belting Company, please let me know.

1895 Ward Maps on a second site /

I have already posted a link to these ward maps at the Community Heritage Maps site, but here is a second source for the maps. This site has the advantage of a large-scale zoomable viewer without the watermarked logo obscuring most of the map. Plate 21 is the Eliot Square area, 35 has Highland Park.

Dennison /

The brick Dennison plant shown in the 1895 map was there until at least 1931. Regarding the Hine photos: by that time, Dennison still owned the property, but it was a furniture factury. It may have been leased out to another company. And Hine using this as an example of child labor was pretty silly. The kids were probably tying string on to paper labels - not exactly brutal work. And his caption ‘Working in the hot sun’ shows just how hard he was working on the propaganda angle. If they were playing in the same hot sun, would it be an issue? Hine did some good work, but this wasn’t part of it.

By the way - Tumblr wasn’t the best choice. This is a painful way to have to make comments. Google or Wordpress blogs would have been better.