Some names are immediately recognizable to all Fort Hill residents. Alvah Kittredge, William Lloyd Garrison, John Eliot, and Nathaniel Bradlee all roll off our tongues. But one of our most long-lived family names has been largely forgotten, with the nothing but a cul-de-sac to remind us of their past glory.

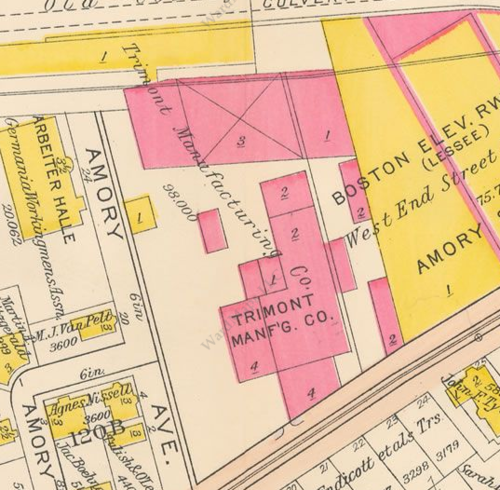

The cul-de-sac, of course, is Thwing Street, a short stub of a street etched into the steep slope of the hill off Highland Street just before it meets Marcella. It represents all that is left of the once-grand Thwing estate, shown here in 1873 at the height of its glory.

The Thwing name goes all the way back to the early years of the Puritans. In 1635 young Benjamin Thwing, at the tender age of 16, hitched a ride across the Atlantic along with his wife Dorothy (who may have had to ride on a separate boat) as a servant or apprentice to Ralph Hudson in Boston. He and Dorothy had seven children, and those children that survived had broods of children of their own, and so on until the Thwing name was spread across the young country. We know all this because in the eighth generation of Thwings there was a man named Walter Eliot Thwing (note the Eliot name, a nod to Roxbury history).

Walter Thwing was a genealogist of the first order, and in an era without the internet or Fedex or telephones he was able to catalog the lives and fates of hundreds of his relatives, including a fair bit of research into the Thwing name in the UK. His magnum opus, Thwing : a genealogical, biographical and historical account of the family, takes us deep into the family history and its relationship with Roxbury circa 1883. Some 20 years later, he published the History of the First Church of Roxbury.

Walter was a true son of Roxbury. According to his brief autobiographical statement in the genealogy, he was born in a boarding house on Cedar St., went to a series of local private schools before attending Roxbury Latin, and managed to get into Harvard before he dropped out to work for his father. The day after Christmas, 1870, he boarded a ship bound for California and kept on going around the world with stops in China, Japan, India, Egypt, mainland Europe, and England before returning home two years later. He claims to have been the youngest man ever to have been around the world at that time. He lived at the family estate on Highland Street with the brief exception of a move to JP for a few years at the end of the 1870s.

Walter’s interest in history was not to be outdone by his sister Annie Haven. Born on the auspicious date of July 4, 1851, Annie’s love of history bordered on the obsessive. She is well-known among historians for her book, The Crooked and Narrow Streets of Boston 1630-1822, but probably should be better known to the rest of us as the author of the classic children’s story Chicken Little. Her crowning achievement, though, was her creation of a massive 74-drawer card catalog detailing every bit of the history of Boston she could track down. Thanks to the wonders of computers, historians can now use a searchable database of her work as they research Boston history. She also created a 3-D model of the City of Boston as it looked in 1775 and traced back her family on the Haven name as far back as 1372. Ms. Thwing lived in Fort Hill, probably at the family house at 65 Beech Glen Street, until her death in 1940. She is buried at the Forest Hills Cemetery in the family plot. The Forest Hills Trust has a more detailed bio of her at this link. She also warrants her own page on wikipedia.

65 Beech Glen Street, the home of Annie Haven Thwing, as it appeared in the April 2, 1881, edition of American Architect and Building News.

Walter and Annie were the children of Supply Clap Thwing. The wonderfully-named man was born on October 27, 1798, in what is now Post Office Square. Supply Clap was a family name; according to the meticulous records of his son he was named for a distant ancestor, Roger Clap, who, “during a famine in the town, had a son born on the same day supplies were received from England, and showed his gratitude by naming his son Supply Clap.”

SC Thwing was a well-to-do man with businesses in the mercantile trades between the East Indies and New Orleans, partial ownership shares of ships, and even business in the coal trade later in his life. He moved to Roxbury in 1824 and never left. He was a pillar of the community, becoming a deacon of the first church, a trustee of Roxbury Latin, and a VP of a local bank, the Institution for Savings in Roxbury and Vicinity. He and his family lived in a beautiful house at 177 Highland at the corner of Beech Glen and Highland St, sadly long gone and replaced by a somewhat drab triple decker on roughly the same spot. He’s seen below standing in front of the wall. Annie Haven and Walter are on the steps.

One final note about Supply Clap: He was a dear friend of Caleb Fellowes, the subject of a future post. When Supply found out that Mr. Fellowes had arranged to leave him a large part of his fortune as part of his will, SC urged him to leave the money to charity instead. That money became the endowment for the Fellowes Athenaeum, known to you and me as the original Dudley branch of the Boston Public Library.

By 1895, the Thwing Estate had been largely sold off and built out and Thwing Street had been added to the maps.